|

The

Regulating Act (1773)

|

Although

both the shareholders of the English East India Company and the British

Government gained, the position of the people of Bengal became most unhappy.

The people were the victims of famine and the corruption of the servants of the

company. According to Lecy, “Never before had navies experienced a tyranny

which was at once so skillful, so searching and so strong. Whole districts which

had been populous and flourishing were at last utterly depopulated, and it was

noticed that on the appearance of a party of English merchants the villages

were at once deserted and the shops shut, and the roads thronged with

panic-stricken fugitives.” According to Chathan, “India teems with

inequities so rank as smell to earth and heaven.” The things were so rotten

that in April 1772 was appointed a select Committee of 31 members to inquire

into the affairs of the East India Company. In August of the same year, the

English East India Company asked for a loan from the British Government. The Parliament

appointed a select committee to examine the affairs of the Company and submit

its report. The committee submitted to final report in May 1773. It was then

that the parliament passed the Regulating Act of 1773.

There were

other causes also which were responsible for the passing of the Regulating Act.

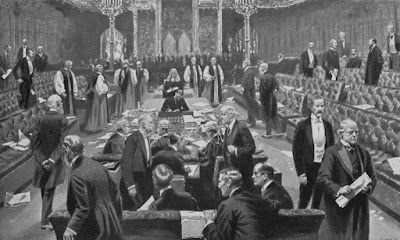

Educated public opinion in England through the press and the floor of

Parliament began to ask for control by the State over the political activities

of the English East India Company. The factors which influenced public opinion

were the abuses of the Company’s rule in India and the attempts made by the ‘Nobobs’

to dominate English society. The British country-gentry not only hated the ’Nobobs’

but also felt jealous of them. Moreover, thee were rival parliamentary

interests which clashed over the question of India. They were primarily

interested in the rise and fall of ministries whose fate depended considerably on

the support of the Directors of the English East India Company who had their

interests in the House of Commons. Regulation and control by the State during

the period 1773-1784 was due largely to the manipulation of the political

machine.

(1) The Regulating Act gave the right of vote for

the election of Directors of the Company to shareholders holding stock worth

1000 pound for 12 months preceding the date of election. Formerly, Directors

were elected for one year but the Act provided that in future they were to be

elected for 4 years. However, one-fourth of them were to retire every yer. The Directors

were required to submit copies of letters and advice received from the governor-General-in-Council.

Copies of letters relating to revenue were to be sent to the Treasury and those

relating to civil and military affairs were to be sent to one of the

Secretaries of State. Governor-General of Bengal and the Governor of Bombay and

Madrasa were required to pay due obedience to the orders of the Directors and

also Keep them constantly informed of all the matters affecting of the

interests of the Company.

(2) Provision

was made for a Governor-General of Bengal and his Council of 4 members. They were

vested with “the whole civil and military Government of the said Presidency,

and also the ordering, management and government of territorial acquisitions

and revenues in the kingdom of Bihar Bengal and Orissa. Warren Hastings was

appointed the first Governor-General of Bengal and Clavering, Monsan, Philip

Francis and Barewell were appointed the members of his council. Members of the

Council were to hold office for 5 years and they could not be removed except by

Crown on the representation of the Directors. Governor-General of Bengal was

required to carry on the work according to the majority opinion of this

Council. He could not over-rule the majority view of this Council. However, he

was given a casting vote in the case of a tie. Governor-General was also given

the power of superintending and controlling the Presidencies of Madras and

Bombay. However, in case of emergency and direct orders from the Directors in

London, Presidencies of Madras and Bombay were not to act according to the orders

of the Governor-General of Bengal.

(3) Governor-in-Council of Bombay and Madras were required to pay due obedience to the orders of

Governor-General of Bengal. They were required to submit to the

Governor-General-in-Council advice and intelligence on transactions and matters

relating to the government, revenues and interests of the Company. They were

required to forward all rules and regulations framed by them to the Governor-General-in-Council,

or did not perform their duties properly, they could be suspended by the

Governor-General-in-Council.

(4) Governor-General-in-Council

was given the power to make rules, ordinance and regulations for the good order

and civil government of Company’s settlement at Fort William and factories and

places subordinate to it. These rules and regulations were not to be against

the laws of England and were required to be registered with the Supreme Court. These

could be disallowed by the king-in-council within two years.

(5) The Regulating

Act provided for a Supreme Court with a Chief justice and three puisne judges.

Sir Elijah Impey was appointed the Chief Justice. The Supreme Court was given

the power to try civil, criminal, admiralty cases. It was to be a Court of

Record and Court of Oyer and Terminer and Gaol delivery in and for the town of

Calcutta, Fort William and other factories subordinate to it. The jurisdiction

of the Supreme Court was to extend to all the British subjects residing in

Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. It was empowered to try all cases of complaints

against any of His Majesty’s subjects for crimes or oppressions. It was to try

suits, complaints or actions against any person in the employment of the

Company or His Majesty’s subjects. It was given both original and appellate

jurisdiction. Cases were to be tried by means of a jury.

(6) The Regulating

Act prohibited the receiving of presents and bribes by the servants of the

Company. “No person holding or exercising any civil or Military office under

the Crown shall accept, receive or take directly or indirectly any present,

gift, donation, gratuity or reward, pecuniary or otherwise.” It was made clear

that the offenders were to make double payment and were liable to be transported

to England.

(7) No British

subject was to charge interest at a higher than 12 per cent. If the

Governor-General, governor, Member of the Council, a judge of Supreme Court or

any other servant of the Company committed any offence he was liable to be

tried and punished by the king’s Bench in England. The act also settled the

salaries of the Governor-General, governor, Chief Justice and other Judges. Thus,

Governor-General was to get 25000 Pound annually. Every member of the Council

was given 10000 pound a year. The annual salary of the Chief Justice was fixed

at 8000 pound and that of an ordinary judge 6000 pound.

It is

universally admitted that the Regulating Act had many shortcomings –

(1) A serious

defect of the Regulating Act was that it did not define clearly the exact

jurisdiction and powers of the Governor-General, the members of his council and

the Supreme Court. Whether the omission was deliberate or unintentional, there

was a lot of conflict. The relations between the Governor-General and the

Supreme Court were never happy. The result was that they always pulled in

different directions.

(2) The Supreme

Court claimed to serve writs on the inhabitants of the country and make them

appear before itself. Warren Hastings resisted this claim of the Supreme Court.

In the case of Cassijurah, the Sheriff and the officers accompanying him were

prevented by a company of Sepoys from executing a writ against the Raja. These

sepoys maintained that they were merely acting under the orders of the Governor-General.

(3) Supreme Court

claimed to have jurisdiction over the collectors of revenue of the Company for

the wrongs done by them in their official capacity. It also claimed to try

judicial officers of the Company for similar wrongs. It refused to recognize the

jurisdiction of the provincial or country courts. It released a district

treasurer who was imprisoned on a charge of embezzlement and remarked thus: “We

know not what your Provincial Chief and the Council are: you might just as well

have said that he was confined by the king of Fairies.” Warren Hastings tried

to remove this conflict by appointing Sir Elijah Impey as the judge of the

Sadar Diwani Adalat. However, this arrangement did not last long because Impey

was called back home. The Regulating Act did not specify as to which law was to

be applied by the Supreme Court. It was a moot point as to whether the Hindu

law, Mohammedan law, Christian law or the English law was to be applied. It was

also not made clear as to whether the law of the defendant was to be applied or

that of the plaintiff in case the two professed different religions. As a

matter of fact, the judges of the Supreme Court knew only the English law and

applied the same practically in every case. Evidently, this had very

unfortunate results.

(4) The Regulating

Act did not contain any answer to many questions. It was not clearly defined as

to who the servants of the English East India Company were and what actually

constituted employment under the Company. A question could be asked as to

whether farmers of revenue could be considered as servants of the Company.

(5) The Regulating

Act made the position of the governor-General very weak. As a matter of fact he

was merely at the mercy of the majority of the members of his council. We are

told that for 6 years there was a big struggle between the Governor General and

the members of his Council. He was outvoted and over-ruled and on many

occasions had to follow a policy which he did not approve of. It was only after

the death of Monson and Clavering that Warren Hastings was able to manage his

Council. Previous to this, his position was so hard that at one time he

actually instructed his agent in London to tender his resignation to the Directors.

(6) The raising

of the qualifications of the voter from 500 to 1000 pound converted the Court

of Director into an oligarchy. About 1246 holders of stock were disfranchised. “The

whole of the regulations, concerning the Court and proprietors, relied upon two

principles, which have proved fallacious, namely, that small numbers were a

security against faction and disorder and that integrity of conduct would

follow the greater property.”

(7) The control of Bengal over Madras and Bombay

was not effective.

(8) According

to Pouten Rouse, “The object of the Act was good, but the system that it

established was imperfect.”

(9) According

to the Report on Indian constitutional Reforms of 1918, the Regulating Act, “created

a Governor-General who was powerless before his own council and an executive

that was powerless before a Supreme Court, itself immune from all

responsibility for peace and welfare of the country- a system that was made workable by the genius and fortitude of one great man.”

(10) The Regulating

Act made a bold attempt at securing good Government in the Company’s territory

in India without the Crown’s directly assuming the responsibility for the same.

The Regulating

Act was the first of a long series of acts passed by Parliament to change and

regulate the Government of India. It made a beginning in the system of a

written constitution for British India. The right of the Parliament to

interfere into the affairs of the company and to legislate for the possessions

was recognized. It is a landmark in the transfer of power from the company to

Parliament. The Act established a collegiate rule in place of “one-man rule.” It

recognized the political functions of the Company. According to Lyall, “The

system of administration set up by the Act of 1773 embodied the first attempt at

giving some definite and recognizable form to the vague and arbitrary ruler ship that had developed upon the Company. From that time forward, the outline of

Anglo-Indian Government was gradually filled in.”

0 टिप्पणियाँ:

एक टिप्पणी भेजें

THANKS FOR YOUR COMMENTS

टिप्पणी: केवल इस ब्लॉग का सदस्य टिप्पणी भेज सकता है.